As the United States enters its third holiday season navigating a potential increase in COVID-19 cases as well as other respiratory illnesses, federal data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show that as of November 9, 2022, 80% of the total population in the United States have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine and only 10% of eligible individuals have received the updated, bivalent booster that was authorized for use among individuals 5 years of age and older in early Fall 2022. Individuals who have not received any booster dose are at higher risk of infection from the virus, and people who remain unvaccinated continue to be at particularly high risk for severe illness and death.

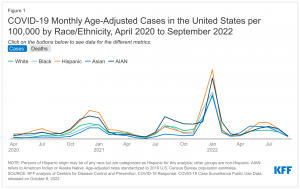

Over the course of the pandemic, racial disparities in cases and deaths have widened and narrowed. However, overall, Black, Hispanic, and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) people have borne the heaviest health impacts of the pandemic, particularly when adjusting data to account for differences in age by race and ethnicity. While Black and Hispanic people were less likely than their White counterparts to receive a vaccine during the initial phases of the vaccination rollout, these disparities have narrowed over time and reversed for Hispanic people. Despite this progress, a vaccination gap persists for Black people. COVID-19 outpatient treatments, which can mitigate hospitalization and death from COVID-19, are also available. However, early data suggest racial disparities in access to and receipt of these treatments.

This data note presents an update on the status of COVID-19 cases and deaths, vaccinations, and treatments by race/ethnicity as of Fall 2022, based on federal data reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

What is the status of COVID-19 cases and deaths by race/ethnicity?

Racial disparities in COVID-19 cases and deaths have widened and narrowed over the course of the pandemic, but when data are adjusted to account for differences in age by race/ethnicity, they show that AIAN, Black, and Hispanic people have had higher rates of infection and death than White people over most of the course of the pandemic. Early in the pandemic, there were large racial disparities in COVID-19 cases. Disparities narrowed when overall infection rates fell. However, during the surge associated with the Omicron variant in Winter 2022, disparities in cases once again widened with Hispanic (4,341 per 100,000), AIAN (3,818 per 100,000), Black (2,937 per 100,000), and Asian (2,755 per 100,000) people having higher age-adjusted infection rates than White people (2,693 per 100,000) as of January 2022 (Figure 1). Following that surge, infection rates fell in Spring 2022 and disparities have once again narrowed. However, as of September 2022, the age-adjusted COVID-19 infection rates were still highest for Black and Hispanic people (192 per 100,000 for each group), followed by AIAN people at 188 per 100,000. White and Asian people had the lowest infection rates at 164 per 100,000 and 153 per 100,000, respectively. While death rates for most groups of color were substantially higher compared with White people early on in the pandemic, since late Summer 2020, there have been some periods when death rates for White people have been higher than or similar to some groups of color. However, age-adjusted data show that AIAN, Black, and Hispanic people have had higher rates of death compared with White people over most of the pandemic and particularly during surges. For example, as of January 2022, amid the Omicron surge, age-adjusted death rates were higher for Black (37.4 per 100,000), AIAN (34.7 per 100,000), and Hispanic people (29.9 per 100,000) compared with White people (23.5 per 100,000) (Figure 1). Following that surge, disparities narrowed when death rates fell. As of August 2022, age-adjusted death rates were similar for AIAN (4.9 per 100,000), Black (4.4 per 100,000), and White people (4.2 per 100,000) and lower for Hispanic (3.6 per 100,000) and Asian (2.7 per 100,000) people. Despite these fluctuations over time, total cumulative age-adjusted data continue to show that Black, Hispanic, and AIAN people have been at higher risk for COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths compared with White people.